Introduction to OOP

- Version 1: C++ without

structs - Version 2: C++ with

structs (data grouping) - Version 3: C++ with

structs (data + logic grouping) - Shapes

In this tutorial we will explore three different example applications, using three different versions:

- version 1: free functions (no

structused). - version 2:

structare used to group the related variables. - version 3:

structare used to group the related variables and functions.

Before starting, please join to this assignment to get a starter template that we will implement our examples in:

Version 1: C++ without structs

After cloning, change directory cd to the repository, then go to cpp-no-struct folder:

cd your_repository_name

cd cpp-no-struct

Example: Euclidean Distance

Consider an application that computes the euclidean distance between two points as following:

\[\begin{equation} \bar{ || p_1p_2 ||} = \sqrt{ (x_1-x_2)^2 + (y_1-y_2)^2 } \end{equation}\]In a single command, let the VS Code create a new file in the current working directory and name it euclidean.cpp.

code euclidean.cpp

Now let’s start writing the boilerplate code for a typical C++ application, if you are not so familiar, copy the following code to your editor:

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

return 0;

}

The three lines you see, if you don’t know their purpose:

#include <iostream>, we need this library file that has the following objects:std::cinto get the two points coordinates from the user through the terminalstd::coutto print the results in the terminal

int main(), as all the programs in the universe starts their work from the main function.return 0, this tells the user who run the program that the program ended successfully without a crash.

Now let’s make a function that takes 4 values that correspond to (x1, y1, x2, y2) and returns the euclidean distance.

To declare a function, you need to use the following

syntax return_type function_name( input1_type input1, input2_type input2, ...) which corresponds to the following components:

return_type: the type of the results that the function returns, if it doesn’t return anything, then usevoid(no type).function_name: the function name, so we can use that name when we need to call that function.- The declaration of the input parameters that this function operates on.

For either a variable name, function name, namespace name, you should consider few rules to have a valid name:

- Alphanumeric: the name doesn’t start with a number.

- The name doesn’t contain spaces.

- The name is not reserved or used before.

int x = 0; // x is valid name

int sum 3 = 0; // invalid name (spaces)

int sum3 = 0; // valid

int sum array = 0; // invalid name (spaces)

int sumArray = 0; // valid

For a function that computes an euclidean distance, we need to declare a function as such:

#include <iostream>

#include <cmath> // We need this library to use the std::sqrt function

double euclideanDistance( double x1, double y1, double x2, double y2)

{

// Self practicing: try to implement this yourself

}

int main()

{

return 0;

}

Now we need to take the input from the user:

#include <iostream>

#include <cmath>

double euclideanDistance( double x1, double y1, double x2, double y2 )

{

double dx = x1 - x2;

double dy = y1 - y2;

return std::sqrt( dx * dx + dy * dy );

}

int main()

{

double px = 0;

double py = 0;

double qx = 0;

double qy = 0;

std::cout << "Enter the two points coordinates as following: x1 y1 x2 y2 [ENTER]\n";

std::cin >> px >> py >> qx >> qy;

std::cout << euclideanDistance( px , py, qx , qy) << "\n";

}

Now let’s compile and run:

g++ euclidean.cpp -o distance

./distance

Enter the two points coordinates as following: x1 y1 x2 y2 [ENTER]

Now the application waits us to enter the values of the coordinates. Let’s try the following:

1.5 1 4.5 5

5

Example: 2D Shapes Distances

Consider an application that computes the area of a given circle, rectangle, triangle, or square on the 2D space.

Let’s make a new file for the new application and we name it area.cpp, using the following command:

code area.cpp

Let’s add the following boilerplate lines:

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

return 0;

}

It will be very wise to have our logic functions in separate header file, so we can that header file for any application we need. So, let’s create another file and call it shapes.hpp, using the following command:

code shapes.hpp

Moreover, we wish to have our functions in a fancy and representative namespace; what about geometry as a namespace?

So our new header file new looks like this:

#ifndef SHAPES_HPP

#define SHAPES_HPP

#include <cmath>

namespace geometry

{

// Our functions go here!

}

#endif

Inside the namespace geometry, let’s implement functions that computes the area for several shapes:

double squareArea( double side )

{

// Implement here please

}

double rectangleArea( double width, double height )

{

// Implement here please

}

double triangleArea( double base, double height )

{

// Implement here please

}

double circleArea( double radius )

{

// Implement here please

}

Let’s return to our main function in the area.cpp. We can make an interesting main function that receives the input from the terminal through the command line and accordingly prints the appropriate output. We wish to have the application that responds to the terminal as following:

$ ./area circle 4

> area: 50.2655

$ ./area rectangle 3 4

> area: 12

$ ./area triangle 3 4 5

> area: 6

$ ./area donuts 4 5

> Undefined shape! donuts

First, in order to make our main function work with command line arguments, we need to modify it to be as following:

#include <iostream>

int main( int argc, char **argv )

{

return 0;

}

Secondly, we would expect that the shape name will be received in argv[1]. For the sake of simplicity, let’s also use std::string in order to make string comparisons. We will later in this series explain the std::string with elaboration. This way we can store the shape name into the std::string and make 4 if conditions. Finally, don’t forget to include shapes.hpp.

#include <iostream>

#include <string> // for std::string

#include "shapes.hpp"

int main( int argc, char **argv )

{

std::string shape = argv[1]; // this will copy the contents pointed by `argv[1]`

double area = 0;

if( shape == "circle" )

{

double radius = std::atof( argv[2] );

area = geometry::circleArea( radius );

}

else if( shape == "square" )

{

double length = std::atof( argv[2] );

area = geometry::squareArea( length );

}

else if( shape == "rectangle" )

{

double width = std::atof( argv[2] );

double height = std::atof( argv[3] );

area = geometry::rectangleArea( width , height );

}

else if( shape == "triangle" )

{

double a = std::atof( argv[2] );

double b = std::atof( argv[3] );

double c = std::atof( argv[4] );

area = geometry::triangleArea( a, b, c );

}

else

{

std::cout << "Undefined shape! " << shape << "\n";

exit( EXIT_FAILURE );

}

std::cout << "area: " << area << std::endl;

return 0;

}

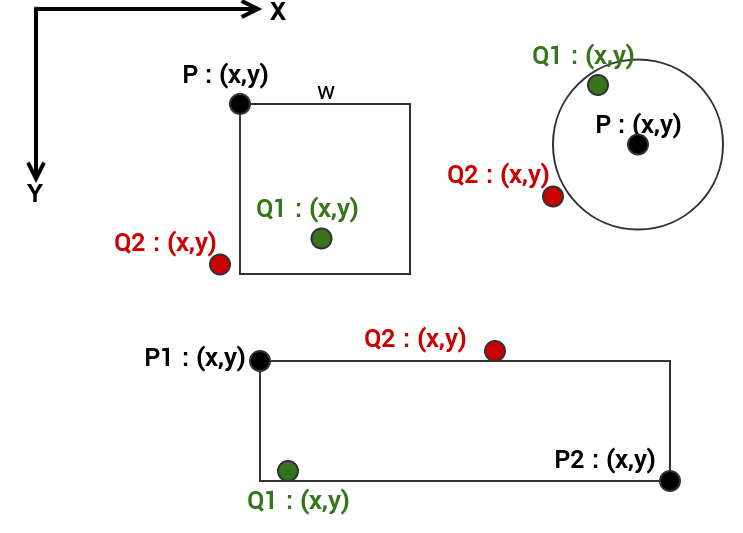

Let’s imagine a more advanced application in the 2D space on our shapes. We need an application to test whether a point q is contained in a given shape or not. For example the following figure illustrates our purpose.

We need a function that takes a shape defined in the 2D space and a given test point, then returns true if the test points lies inside the shape and false otherwise.

Let’s implement our functions inside the namespace geometry

bool circleContains(double centerX, double centerY, double radius, double testX, double testY)

{

double dx = centerX - testX;

double dy = centerY - testY;

return dx * dx + dy * dy <= radius * radius;

}

bool squareContains(double upleftX, double upleftY, double length, double testX, double testY)

{

return testX >= upleftX &&

testX <= upleftX + length &&

testY >= upleftY &&

testY <= upleftY + length;

}

bool rectangleContains(double upleftX, double upleftY, double downRightX, double downRightY,

double testX, double testY)

{

return testX >= upleftX &&

testX <= downRightX &&

testY >= upleftY &&

testY <= downRightY;

}

Feel free to make an interesting application source file (with main function) to use the above functions.

Example: DNA Base Counter

We have already worked in this example in our assignment. So let’s directly implement the DNA base counter in a separate file called dna.hpp.

From the terminal create and open the file.

code dna.hpp

The file then should look like:

#ifndef DNA_HPP

#define DNA_HPP

namespace dna

{

char complementaryBase(char base)

{

// Copy from assignment 3

}

char *complementarySequence(char *base, int size)

{

// Copy from assignment 3

}

int countChar(char *base, int size, char test)

{

// Copy from assignment 3

}

} // namespace dna

#endif

Version 2: C++ with structs (data grouping)

For this part, we will realize the benefits of using struct for grouping related data. Now change directory to cpp-data-struct that is in the upper directory:

cd ../cpp-data-struct

Initially, let’s copy the header file shapes.hpp from the previous directory so develop on it incrementally:

cp ../cpp-no-struct/shapes.hpp .

Let’s do the same with dna.hpp:

cp ../cpp-no-struct/dna.hpp .

structs offer us a great advantage that we will use in this part: grouping related variables into a new user-defined type.

Let’s discuss the possible variables that we can group from the previous tasks.

A 2D Point

We have extensively worked with coordinates in the first two examples, and every coordinate was represented by two values: x and y. So, it would be a great deal to use struct for grouping x and y into a custom user-defined type. Let’s add this type declaration into namespace geometry for consistency:

struct Point

{

double x;

double y;

};

Shapes

In the second example, considering the application that tests whether a point lies in a given shape, each shape was represented by at least one point (x and y) and a dimension:

- The circle was represented by the center point and the radius.

- The rectangle was represented by two points (an alternative representation is a point plus the width and the height).

- The square was represented by the left upper corner and the side length.

By using struct, we could have grouped the related data of each shape in the following way:

struct Circle

{

Point center;

double radius;

};

struct Square

{

Point upLeftCorner;

double length;

};

struct Rectangle

{

Point upLeftCorner;

Point downRightCorner;

};

Realize that we have used the Point, which is already declared, as a member in our shapes.

Example: Euclidean Distance

By using struct, we can use a more concise and descriptive version of euclideanDistance function:

double euclideanDistance( double x1, double y1, double x2, double y2 )

{

double dx = x1 - x2;

double dy = y1 - y2;

return std::sqrt( dx * dx + dy * dy );

}

double euclideanDistance( Point p1, Point p2 )

{

double dx = p1.x - p2.x;

double dy = p1.y - p2.y;

return std::sqrt( dx * dx + dy * dy );

}

DRY Solution

We can adopt DRY solution for such an overload:

double euclideanDistance( double x1, double y1, double x2, double y2 )

{

double dx = x1 - x2;

double dy = y1 - y2;

return std::sqrt( dx * dx + dy * dy );

}

double euclideanDistance( Point p1, Point p2 )

{

return euclideanDistance( p1.x, p1.y, p2.x, p2.y );

}

Example: 2D Shapes Distances

We can add overloaded function for the second example as following inside namespace geometry:

bool circleContains(Circle c, Point test)

{

// Implement yourself.

// DRY solution?!

}

bool squareContains(Square s, Point test)

{

// Implement yourself.

// DRY solution?!

}

bool rectangleContains(Rectangle r, Point test)

{

// Implement yourself.

// DRY solution?!

}

Example: DNA Base Counter

Same inside namespace dna:

struct DNA

{

char *base;

int size;

};

char *complementarySequence( DNA &dna )

{

// DRY solution

return complementarySequence( dna.base, dna.size );

}

int countChar( DNA &dna, char test)

{

// DRY solution

return countChar( dna.base, dna.size, test);

}

Version 3: C++ with structs (data + logic grouping)

In the last part, we are going to achieve a big advantage and create our first living objects that bundles the related data as well as the related functions that operates on these data.

First, let’s move to our final directory:

cd ../cpp-struct

In the previous part, we have realized some structs that bundles data into a user-defined type and related free functions that operate on these types.

Point

For the point, we had the following struct

struct Point

{

double x;

double y;

};

and the following free function that operates on two given Points:

double euclideanDistance( Point p1, Point p2 )

{

double dx = p1.x - p2.x;

double dy = p1.y - p2.y;

return std::sqrt( dx * dx + dy * dy );

}

Now, we can join the above free function into the struct Point, but this time, we don’t need to provide two points, we will instead provide a single one:

struct Point

{

double euclideanDistance(Point p)

{

double dx = x - p.x;

double dy = y - p.y;

return std::sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

double x;

double y;

};

To be more accurate, we should now refer to euclideanDistance as a method, not a free function. A method is a function that is contained in struct/class and operates on the object data. So, inside euclideanDistance we can access the current point data by using their names directly.

In the main function we can now use the Point object as following:

int main()

{

geometry::Point p1, p2;

std::cout << "Enter the two points coordinates as following: x1 y1 x2 y2 [ENTER]\n";

std::cin >> p1.x >> p1.y >> p2.x >> p2.y;

std::cout << p1.euclideanDistance( p2 );

}

By the way, it would be also correct if we flipped it that way p2.euclideanDistance( p1 ).

Shapes

Similarly, for each shape, we can group the related data of the shape alongside the functions that exclusively operate on that shape.

Circle

In the previous part, we had the Circle type with the following declaration:

struct Circle

{

Point center;

double radius;

};

Also, we had two functions that operate on the circle:

double circleArea( double radius )

{

return radius * radius * M_PI;

}

bool circleContains(double centerX, double centerY, double radius, double testX, double testY)

{

double dx = centerX - testX;

double dy = centerY - testY;

return dx * dx + dy * dy <= radius * radius;

}

We could have grouped all together inside the struct Circle as following:

struct Circle

{

double circleArea()

{

return radius * radius * M_PI;

}

bool circleContains( Point test )

{

double dx = center.x - test.x;

double dy = center.y - test.y;

return dx * dx + dy * dy <= radius * radius;

}

Point center;

double radius;

};

Having circleArea and circleContains inside a struct Circle may pose a redundancy in names. So we can make it more fancy to modify the names as following:

struct Circle

{

double area()

{

return radius * radius * M_PI;

}

bool contains( Point test )

{

double dx = center.x - test.x;

double dy = center.y - test.y;

return dx * dx + dy * dy <= radius * radius;

}

Point center;

double radius;

};

We apply the same actions on Rectangle, Square, and Triangle.

Rectangle

struct Rectangle

{

double area()

{

return width * height;

}

bool contains(Point test)

{

return test.x >= corner.x &&

test.x <= corner.x + width &&

test.y >= corner.y &&

test.y <= corner.y + height;

}

Point corner;

double width;

double height;

};

Square

struct Square

{

double area(double side)

{

return length * length;

}

bool contains(Point test)

{

return test.x >= corner.x &&

test.x <= corner.x + length &&

test.y >= corner.y &&

test.y <= corner.y + length;

}

Point corner;

double length;

};

Triangle

struct Triangle

{

double triangleArea()

{

double s = (a + b + c) / 2;

return std::sqrt(s * (s - a) * (s - b) * (s - c));

}

double a;

double b;

double c;

};

New area application

After we used struct that bundles the related data with the related methods, we now can use our main function as following:

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

std::string shape = argv[1]; // this will copy the contents pointed by `argv[1]`

double area = 0;

if (shape == "circle")

{

geometry::Circle circle;

circle.center = {0, 0};

circle.radius = std::atof(argv[2]);

area = circle.area();

}

else if (shape == "square")

{

geometry::Square square;

square.corner = {0, 0};

square.length = std::atof(argv[2]);

area = square.area();

}

else if (shape == "rectangle")

{

geometry::Rectangle rectangle;

rectangle.corner = {0, 0};

rectangle.width = std::atof(argv[2]);

rectangle.height = std::atof(argv[3]);

area = rectangle.area();

}

else if (shape == "triangle")

{

double a = std::atof(argv[2]);

double b = std::atof(argv[3]);

double c = std::atof(argv[4]);

geometry::Triangle triangle{a, b, c};

area = triangle.area();

}

else

{

std::cout << "Undefined shape! " << shape << "\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

std::cout << "area: " << area << std::endl;

return 0;

}